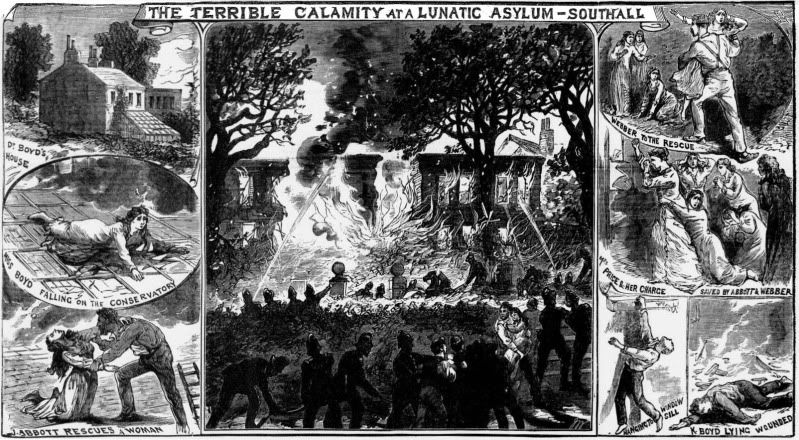

In 1883, there was a terrible fire at the Southall Lunatic Asylum, causing both loss of life and property:

The Times August 15 1883

FATAL FIRE AT A LUNATIC ASYLUM.

Early yesterday morning a fire was discovered at Southall-park, the mansion of which has for some time past been used as a private lunatic asylum. The building was erected by Sarah Jennings, Duchess of Marlborough, and was first inhabited by Sir W. Ellis, at one time medical superintendent of the county lunatic asylum at Hanwell. It subsequently came into the occupation of Dr. Stewart, who was succeeded by Dr. Boyd, formerly superintendent at the Marylebone Workhouse, and afterwards of the Bath and Somerset Asylum. He had occupied Southall-park about eight years, and received insane persons for private treatment, the average number of his patients being from 20 to 30. The fire was discovered by one of the female attendants shortly after 2 o’clock, and an alarm was at once given throughout the establishment; but owing to the hold which the flames had already obtained on the building, the greatest difficulty was experienced in rescuing the occupants, whose scrams aroused the inhabitants of the neighbouring village, many of whom were quickly in attendance, and rendered all the assistance they possible could. Foremost among these was Mr. James Abbott, son of the late editor and proprietor of the British Beekeepers’ Journal, who, by means of a ladder, entered a window on the first floor, and removed three female patients, whom he found crouching in a corner of the room. Other patients escaped in their night clothes, and were found clustered under the trees in the park, while one was found on the lawn in front of the building in an insensible condition. In the meantime messengers were dispatched to the neighbouring districts summoning the aid of the fire brigades, and within a quarter of an hour from the call, the Hanwell steamer, in charge of Captain Walker Abbott, arrived, but owing to the short supply of water, and its distance from the mansion, they were unable to get to work until the arrival of the Ealing Dean Manual, from which several lengths of hose were borrowed. Other brigades quickly followed, including the Ealing steamer, which, with borrowed hose, quickly got to work. It is remarkable, however, that, connected with an institution of this importance, there should have been so inadequate a supply of water, the nearest supply being from a shallow pond a quarter of a mile from the house. After the arrival of the brigades it was evident that nothing could be done but to save the outlying portions of the building, upon which the firemen directed their efforts, and continued to do so until they were assured that all attempts to save life were futile. Subsequent information proved that at least five bodies, including those of Dr. Boyd and one of his sons, were buried in the debris, and the efforts of the firemen and their numerous assistants were at once directed to the removal of the dangerous walls, prior to the commencement of the search for the missing bodies, which up to a late hour last night were not reached. The missing are:--Dr. Boyd, the proprietor of the asylum; Mr. W. Boyd, who was on a short visit home from Texas; Mrs. Cullimore, a patient; Captain Williams, a patient; and Elizabeth O’Lachlin, a cook. The injured are Elizabeth Howe housemaid, who sustained a serious cut on the head and concussion of the spine; Elizabeth Wilgros, kitchen maid, shock to the system from jumping out of a first-floor window; Mr. H. Boyd, nephew of Dr. Boyd, injury to the foot; and Miss Bronette Boyd, injury to the leg. Mr. Hutton, gardener, who sustained a broken arm, fractured ribs, and slight concussion of the brain, died a few hours afterwards. Drs. Alexander M’Donald, Burton, Willett, and Fenton were indefatigable in their attention to the injuried. Southall, a usually quiet country village, was in a state of great excitement in consequence of the fire; but, through the efforts of an ample contigent of police, under Superintendent Foinett, excellent order was maintained. Estimated damage £25,000. . .

The Times August 15 1883

FATAL FIRE AT A LUNATIC ASYLUM.

Early yesterday morning a fire was discovered at Southall-park, the mansion of which has for some time past been used as a private lunatic asylum. The building was erected by Sarah Jennings, Duchess of Marlborough, and was first inhabited by Sir W. Ellis, at one time medical superintendent of the county lunatic asylum at Hanwell. It subsequently came into the occupation of Dr. Stewart, who was succeeded by Dr. Boyd, formerly superintendent at the Marylebone Workhouse, and afterwards of the Bath and Somerset Asylum. He had occupied Southall-park about eight years, and received insane persons for private treatment, the average number of his patients being from 20 to 30. The fire was discovered by one of the female attendants shortly after 2 o’clock, and an alarm was at once given throughout the establishment; but owing to the hold which the flames had already obtained on the building, the greatest difficulty was experienced in rescuing the occupants, whose scrams aroused the inhabitants of the neighbouring village, many of whom were quickly in attendance, and rendered all the assistance they possible could. Foremost among these was Mr. James Abbott, son of the late editor and proprietor of the British Beekeepers’ Journal, who, by means of a ladder, entered a window on the first floor, and removed three female patients, whom he found crouching in a corner of the room. Other patients escaped in their night clothes, and were found clustered under the trees in the park, while one was found on the lawn in front of the building in an insensible condition. In the meantime messengers were dispatched to the neighbouring districts summoning the aid of the fire brigades, and within a quarter of an hour from the call, the Hanwell steamer, in charge of Captain Walker Abbott, arrived, but owing to the short supply of water, and its distance from the mansion, they were unable to get to work until the arrival of the Ealing Dean Manual, from which several lengths of hose were borrowed. Other brigades quickly followed, including the Ealing steamer, which, with borrowed hose, quickly got to work. It is remarkable, however, that, connected with an institution of this importance, there should have been so inadequate a supply of water, the nearest supply being from a shallow pond a quarter of a mile from the house. After the arrival of the brigades it was evident that nothing could be done but to save the outlying portions of the building, upon which the firemen directed their efforts, and continued to do so until they were assured that all attempts to save life were futile. Subsequent information proved that at least five bodies, including those of Dr. Boyd and one of his sons, were buried in the debris, and the efforts of the firemen and their numerous assistants were at once directed to the removal of the dangerous walls, prior to the commencement of the search for the missing bodies, which up to a late hour last night were not reached. The missing are:--Dr. Boyd, the proprietor of the asylum; Mr. W. Boyd, who was on a short visit home from Texas; Mrs. Cullimore, a patient; Captain Williams, a patient; and Elizabeth O’Lachlin, a cook. The injured are Elizabeth Howe housemaid, who sustained a serious cut on the head and concussion of the spine; Elizabeth Wilgros, kitchen maid, shock to the system from jumping out of a first-floor window; Mr. H. Boyd, nephew of Dr. Boyd, injury to the foot; and Miss Bronette Boyd, injury to the leg. Mr. Hutton, gardener, who sustained a broken arm, fractured ribs, and slight concussion of the brain, died a few hours afterwards. Drs. Alexander M’Donald, Burton, Willett, and Fenton were indefatigable in their attention to the injuried. Southall, a usually quiet country village, was in a state of great excitement in consequence of the fire; but, through the efforts of an ample contigent of police, under Superintendent Foinett, excellent order was maintained. Estimated damage £25,000. . .

Comment